In this text I reproduce the poem If… by Rudyard Kipling, I add three of its translations, and I make my anecdotal, relative, treacherous comments… And this is a translation of a post I published in HispanicLA.

Traduttore traditore

This was repeated by my mother – who was a literature teacher – when she fed me books: traduttore, traditore. She said it in the original Italian – perhaps so she wouldn’t have to translate it and therefore, not to betray it – but with it she gave me the tip of a figment of intelligence to understand that perhaps all translations of poems are vain (But what if the translator is also the author?).

For this reason, if the translation is truly extraordinary, it should be conceived as a new work, born from the translator’s head when reading and rereading and ruminating and possessing the original and thus betraying it in his own particular and unique way. Anyway, the saying, if true, also works in English or Spanish: translator, traitor.

Why If…? It is an exercise. It’s poetry

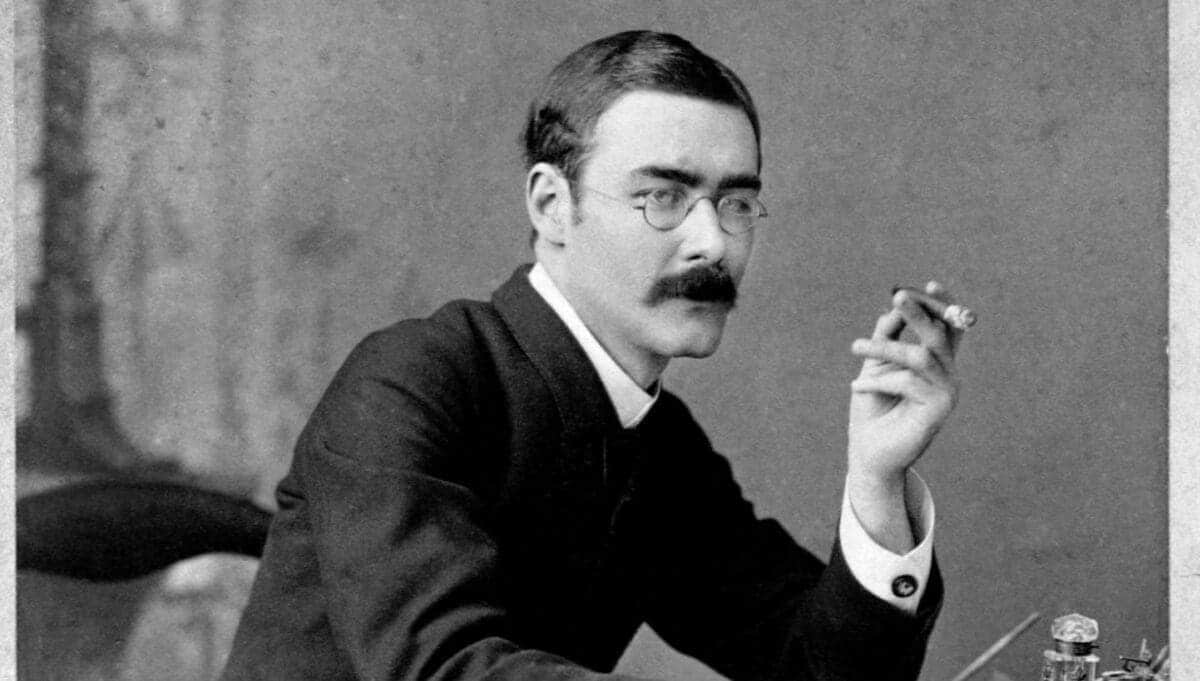

If…, which Rudyard Kipling wrote in 1895, at the age of 30, has a quality that allowed it to endure as a popular poem. Which? Between Poe and the Desiderata that Max Ehrmann wrote in 1920, although it seems to be a text from the Middle Ages, Kipling-the author of the Jungle Book-writes in a single sentence some existentialist and conformist advice to his son John, where he teaches him to be stoic.

Would we repeat it to our son?

The question is open, because Rudyard was faithful to his blindness to the last consequences. He sent John to the Great War even though his health would disqualify him. John died at the age of 18 in France, during the Battle of Loos, in 1915. Does it invalidate the poem? At least, it reduces it to one more text about himself, about the poet, his distortions and prejudices. The son – or the «pigeon» – matters as much in the poem as John’s life does in reality. Not much.

It contains a certain love and good poetry, but it revolts me when the principle followed by those who always advise, nothing more and here more than anything, is «never give up», a cruel, funeral call and, ultimately, totally contrary to what it claims to defend, because it is defeatist and foreboding. Because if after failing, you don’t give up and look for another path, you are doomed to frustration.

The first translation is attributed to a Río Gallegos, and is recommended by some expert or experts on their own… I am not an expert, so I base myself on eyes, ears and reading. As for the translator, I know nothing about him nor did I find traces of his presence, which equates him to multiple translations without attribution. Unless the name refers to the city in Patagonia, Argentina…

The second, by Rafael Squirru, is in Castilian, in Argentine, more than in the language of Spain, and would have appeared alone, without other additions, if it were not for the last word, «pichón», where in an outburst of fidelity to the rhyme , the translator now is a traitor and causes a mess and betrays my appreciation. Why not «hijo mío» and that’s it?

Now: «If …» is part of the debate on machismo and masculinity, to the point that Isabel Campo titled her documentary on the subject with the last verse of the poem.

Yair Lapid and Rudyard Kipling

Yair Lapid, now Israel’s prime minister, a former TV presenter and commentator, translated the poem many years ago. About forty years ago a good friend of that time, Daniel Mordzinski, told me that he and his beautiful partner Gabriela Azar were sheltered, or received, by Tommy Lapid, then a journalist, later a Member of the Knesset, and that the one who impressed him most in that family was this son, a young boy, Iair, of whom someone said that one day he would be the Prime Minister of Israel. And he is now.

Daniel is now respected and well known in Paris as the photographer of the writers, although already in 1982, at the age of 22, he contributed his very original photos of Jorge Luis Borges to a first edition of Alef, the arts and letters magazine in Spanish that I produced in Israel, and then with other photos of Julio Cortázar, on the latter’s death. Finally, my gratitude and admiration for having contributed with his photo of stacked rifles for the cover of my nouvelle Soldiers of Paper.

I have not personally known any of the Lapids, nor did they represent the political side with which I identified, and yet the conjugation of today’s politician with a lover of poetry and, moreover, a good translator is striking.

It is also interesting that the comments after Lapid, already in 2020, published his translation on Facebook, ignore the poem and focus on the political moment of that time and his mission to bring to an end the corrupt government of Netanyahu.

Finally, politics and translation sometimes go hand in hand. Bartolomé Mitre translated Dante’s Divine Comedy in 1897 and later became Argentina’s President.

Original by Rudyard Kipling, reading by Michael Caine

If you can keep your head when all about you

Are losing theirs and blaming it on you;

If you can trust yourself when all men doubt you,

But make allowance for their doubting too;

If you can wait and not be tired by waiting,

Or, being lied about, don’t deal in lies,

Or, being hated, don’t give way to hating,

And yet don’t look too good, nor talk too wise;

If you can dream and not make dreams your master;

If you can think and not make thoughts your aim;

If you can meet with triumph and disaster

And treat those two imposters just the same;

If you can bear to hear the truth you’ve spoken

Twisted by knaves to make a trap for fools,

Or watch the things you gave your life to broken,

And stoop and build ‘em up with wornout tools;

If you can make one heap of all your winnings

And risk it on one turn of pitch-and-toss,

And lose, and start again at your beginnings

And never breathe a word about your loss;

If you can force your heart and nerve and sinew

To serve your turn long after they are gone,

And so hold on when there is nothing in you

Except the Will which says to them: «Hold on»;

If you can talk with crowds and keep your virtue,

Or walk with kings—nor lose the common touch;

If neither foes nor loving friends can hurt you;

If all men count with you, but none too much;

If you can fill the unforgiving minute

With sixty seconds’ worth of distance run

Yours is the Earth and everything that’s in it,

And—which is more—you’ll be a Man my son!

Spanish translation of ‘Río Gallegos’

Si guardas en tu puesto la cabeza tranquila,

cuando todo a tu lado es cabeza perdida.

Si tienes en ti mismo una fe que te niegan

y no desprecias nunca las dudas que ellos tengan.

Si esperas en tu puesto, sin fatiga en la espera.

Si engañado, no engañas.

Si no buscas más odio, que el odio que te tengan.

Si eres bueno, y no finges ser mejor de lo que eres.

Si al hablar no exageras, lo que sabes y quieres.

Si sueñas y los sueños no te hacen su esclavo.

Si piensas y rechazas lo que piensas en vano.

Si alcanzas el Triunfo o llega tu Derrota,

y a los dos impostores les tratas de igual forma.

Si logras que se sepa la verdad que has hablado,

a pesar del sofisma del Orbe encanallado.

Si vuelves al comienzo de la obra perdida,

aunque esta obra sea la de toda tu vida.

Si arriesgas de un golpe y lleno de alegría,

tus ganancias de siempre a la suerte de un día,

y pierdes, y te lanzas de nuevo a la pelea,

sin decir nada a nadie lo que eres, ni lo que eras.

Si logras que los nervios y el corazón te asistan,

aún después de su fuga, en tu cuerpo en fatiga,

y se agarren contigo, cuando no quede nada,

porque tú lo deseas, lo quieres y mandas.

Si hablas con el pueblo, y guardas la virtud.

Si marchas junto a Reyes, con tu paso y tu luz.

Si nadie que te hiera, llega a hacerte la herida.

Si todos te reclaman, y ninguno te precisa.

Si llenas el minuto inolvidable y cierto,

de sesenta segundos, que te llevan al cielo.

Todo lo de esta Tierra será de tu dominio,

Y mucho más aún …

¡Serás un Hombre, hijo mío!

Castillan translation by Rafael Squirru

Si no pierdes la cabeza cuando todos alrededor

La están perdiendo y encima te culpan;

Si te tienes confianza cuando todos te dudan

Aceptando también que te duden,

Si eres capaz de esperar sin que te canse la espera

O calumniado, no caes en la calumnia,

O detestado, no terminas odiando,

Y tampoco te jactas de ser bueno o sabio;

Si puedes soñar sin que tus sueños te dominen;

Pensar, sin hacer del pensamiento tu objetivo,

Si encontrando el Triunfo y el Fracaso

Tratas ambos impostores por igual;

Si puedes soportar que la Verdad que has predicado

Sea torcida por cerdos para embaucar a idiotas,

O ver la labor de tu vida hecha pedazos

Y con herramientas viejas la vuelves a armar;

Si eres capaz de apilar lo que ganaste

Y apostar todo en un «cara o cruz»

Y perder, y empezar de nuevo desde cero

Sin de tu pérdida murmurar un pero;

Si eres capaz de poner corazón, fibra y nervio

A tu servicio aunque ya no estén

Y no obstante, sigues prendido, aun vacío,

Salvo la voluntad que comanda a «No ceder!»

Si hablas con las masas y mantienes tu virtud

O caminas con reyes, conservando lo común;

Si ni rivales ni buenos amigos logran lastimarte

Y puedes brindarte a todos pero a nadie demasiado;

Si puedes llenar el minuto que no perdona

Con sesenta segundos de maratón,

Tuya es la tierra y todo lo que está en ella

Y, lo que es más, serás un hombre, mi pichón!

Hebrew translation of Iair Lapid

תרגומו של יאיר לפיד

אם

אם תדע לשמור על ראש צלול כשכולם סביבך,

מאבדים את ראשיהם ואז מאשימים אותך,

אם תוכל לסמוך על עצמך גם אם בך איבדו אמון,

אבל לקחת בחשבון שהם חושבים שאין לך כיוון;

אם לחכות אתה יודע ולא חשוב לכמה זמן,

או לתת שישקרו אותך, מבלי שתהפוך שקרן,

או שישנאו אותך, מבלי שתהפוך שונא

וגם להיות חכם וטוב מבלי להיראות שונה.

אם אתה יכול לחלום, בלי לתת לחלומות את חייך לנהל,

אם אתה יכול לחשוב, בלי לתת למחשבות את מטרותיך לבלבל;

אם אתה יכול לפגוש בניצחון או באסון

ומול שני המתחזים האלו לנהוג בהיגיון;

אם אתה יכול לסבול כשהמילים אותן אמרת

הופכות מלכודת לטיפשים בידי נוכלים שלא הכרת,

או כשתראה איך נשברים כל הדברים שרק למענם שווה לחיות

ותתכופף, ותאסוף את הכלים הישנים, ושוב תתחיל לבנות

אם תוכל בערימה לאסוף את כל מה שצברת

ולסכן אותה מבלי לחשוב על מה הימרת

ולהפסיד, ולהתחיל שוב מחדש כמו כל ההתחלות

ולעולם על ההפסד לא לעצור לבכות;

אם תוכל להכריח את לבך, את כל העצבים והשרירים

להגן על מטרותיך גם אם קלושים הסיכויים

ולהמשיך גם אם לא נשאר בך שום כוח

מלבד כוח הרצון שעוד אומר לך «אסור לברוח»!

אם תוכל לנאום בפני קהל מבלי להסתחרר,

ולצעוד עם מלכים – אבל פשוט ואנושי להישאר,

אם בחייך יריבים ואוהבים לא יכולים יותר מדי להתערב

אם אליך כל אחד יכול לגשת, אך לא יותר מדי להתקרב;

אם תוכל למלא כל דקה במדויק,

בשישים שניות שלמות של ריצה אל המרחק,

תוכל לרשת את הארץ ואת כל העולם

ועוד יותר מזה, ילדי – תהיה אדם.